Ways Of Seeing, Revisited

On the 50th anniversary of John Berger’s iconic essay on the male gaze in art, we reimagine 'Ways Of Seeing' through a post Me-Too lens

In Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1534), a nude woman reclines seductively on a red chaise lounge, her sultry gaze looking outward from an elegant room. Her posture is languid, one hand draped furtively between her thighs. Epitomizing the Late Renaissance ideal of beauty, she is youthful, buxom, and hairless. Her luminescent skin is a source of light in an otherwise dimly lit room, as white and smooth as the pearl that dangles from her ear. When Titian finished the painting in 1534—commissioned by the Duke of Urbino as a wedding gift to his alarmingly young wife, Giuila da Varano, age 10—he unwittingly created one of the most recognisable subjects in art history: the reclining nude.

In the second episode of seminal 1972 BBC series, Ways of Seeing, art critic John Berger argues that female nudes historically reflected and reinforced the power relationship between the women depicted and the predominantly male audience. Over the course of 30 eye-opening minutes, he illustrates how the conventions of the average European nude—once all the mythological rhetoric and religious allegory had been stripped away—were on par with the conventions of modern advertising, journalism, television and “girlie magazines”, where women are depicted passively to appeal to the implied male spectator. The simple yet salient opening line of the episode bears repeating: “Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.”

La Carità, Francesco Salviati, 1543–1545 (detail); Adam and Eve, Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1528 (detail)

In European art, men were usually the painters or spectator-owners, and women were usually the objects. Most nude paintings show soft, fleshy female bodies in various states of repose. The women are idealised, transformed from human beings into objects of desire, stripped of their own autonomy. As Berger puts it: c

Out of tens of thousands, there are only a handful of nudes in the Western canon—around 20 or 30—that depict their naked subjects as themselves. One such painting is Edouard Manet’s Olympia (1863). Directly inspired by Venus of Urbino, the painting shows a young nude woman reclining in bed, gazing out at the audience, her left hand covering and simultaneously drawing attention to her lap. When Manet’s painting was exhibited in 1865, mass outrage ensued. The public weren’t scandalised by Olympia’s nudity—it was Manet’s refusal to adhere to the centuries-long cardinal rule of idealising the female form that shocked. Manet showed Olympia exactly as she was: a 19th century Parisian prostitute, the kind of woman you were likely to pass on the street. If Venus appears supine, posed, very much on display, Olympia is the opposite: alert and confident, staring at the viewer with a direct and almost confrontational gaze.

“They are not naked as they are, they are naked as you see them.”

The imbalance present in European nudes is so deeply baked into our visual culture that it still affects how many women view themselves today—first and foremost as a sight for men. Women are still routinely nude whereas men aren’t, something writer Naomi Wolf likens to “learning inequality in little ways all day long.” In the documentary, Codes of Gender, sociologist Erving Goffman argues that we may only notice the way women are subjugated through advertisements—through nudity, facial expressions and poses—if we imagine men in the same way and interrogate our reaction. When we put men in the passive positions usually reserved for women, society’s expectations of gender and the way individuals are expected to perform it become startlingly clear.

In Ways of Seeing, Berger identified a splitting of the European woman’s consciousness, in which she must “survey everything she is and everything she does because how she appears to others, and ultimately how she appears to men, is of crucial importance for what is normally thought of as the success of her life.” Women today are still programmed to constantly consider and craft their performance from another perspective, something scholar and civil rights activist WEB Du Bois called double consciousness: “It is a peculiar sensation … this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.”

Primavera, Sandro Botticelli, c.1482 (detail); Venus with a Satyr and Two Cupids, Annibale Carracci, c.1588 (detail)

Coming of age in a small coastal town in the early noughties was a self-conscious time to be alive. Toxic beauty standards were very much the rule and, like most teens, a steady diet of glossy magazines, Victoria’s Secret runway shows, and a rolodex of rail-thin and almost exclusively white pop culture icons ranging from Kate Moss to Paris Hilton, did a tremendously good job at keeping them at the forefront of my mind. Imagine the skills I could have amassed had a sizeable chunk of my mental energy not been frittered away wondering how hot I was to the opposite sex! How much money and anguish I might have saved if I didn’t cave to the allure of products and fad diets promising to eradicate my ‘flaws’!

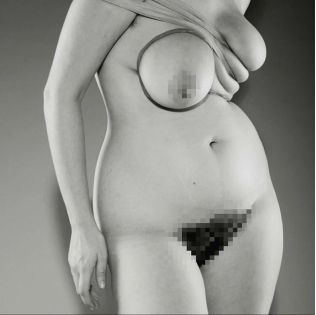

Boobs sprouted on a previously concave chest for me at the tender age of ten. By dint of acquiring these fatty, fibrous mounds of tissue, everyday activities that were once acceptable and still par for the course among my smaller-chested counterparts—walking down the street without a bra, popping to the shops in a string bikini after the beach, v-neck anything—sudden felt inappropriate, indecent, shameful. (Slutty, if we’re going with the popular word choice at the time). It suddenly felt as if my body was up for public consumption and critique. Leaving the blissful innocence of childhood behind, this newfound and unwarranted attention paved the way for the next chapter in life: an acute awareness of my body and the way it was judged and objectified under the male gaze.

In Ways of Seeing, we are shown how images can reveal the criteria and conventions by which women are judged by society at any given time. Through them, we can understand how women were seen. Beauty ideals aren’t static. Like fashion trends, they come and go: voluptuous curves are replaced by waifish frames, pencil-thin eyebrows make way for bushy brows,big butts go from being derided to in-demand. If anyone doubts the dizzying extent to which these standards shift, you only need to look at advertisements from the 1950s that promoted weight gain, replete with scientific ways to “add attractive pounds and inches” and warnings that, “if you want to be popular, you can't afford to be skinny!”. This body image script has since been turned on its head; the insecurities of increasingly savvy modern consumers exploited in subtler yet more pervasive ways.

"Leaving the blissful innocence of childhood behind, this newfound and unwarranted attention paved the way for the next chapter in life: an acute awareness of my body and the way it was judged and objectified under the male gaze."

In 2018, Kim Kardashain—who is largely considered to be the pinnacle beauty standard today with her ethnically ambiguous good looks and unattainable proportions—came under fire when she posted an image of a Flat Tummy lollipop to her 111 Instagram followers, captioning the product as “literally unreal.” The appetite suppressant, it implied, could be thanked for her enviable physique. Unlike most people, Kim Kardashian isn’t just screaming into the void when she posts on social media. Her influence is immense, unavoidable—it can be seen in everything from plastic surgery requests and scholarly debates on the unethical practice of blackfishing, to TikTok videos about #glutepumping and #lipplumping that amass views in the hundreds of millions.

“What is novel is that now, body shape ideals change as quickly as fashions in hairstyles,” Cary Gabriel Costello, an associate professor of sociology and director of LGBTQ+ Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, said in an interview with US Today. “In the noughties, people plucked or lasered their eyebrows into thin arches. Now those same people ‘have to’ go get microblade eyebrow tattoos to have the lush eyebrow look approved today. Every few years now, celebrities and influencers have to go get new plastic surgical procedures on their faces, because if they don't, everyone will see they are wearing an outdated facial style.”

One Western beauty ideal that remains unwavering—forever etched into women’s psyches—is the endless pursuit of youth. “As men see it, a woman’s purpose in life is to be an erotic object,” Simone de Beauvoir says in her 1970 book, The Coming of Age. “When she grows old and ugly, she loses the place allotted to her in society: she becomes a monstrum that excites revulsion and even dread.”

This sentiment is echoed in Susan Sontag’s 1972 brilliant essay The Double Standard of Ageing. In it, she examines how women interiorise society’s contemptuous gaze as they age, their profound sense of shame made more intolerable by the high premium once placed on beauty and youth. “The great advantage men have is that our culture allows two standards of male beauty: the boy and the man,” she says. “The beauty of a boy resembles the beauty of a girl. In both sexes, it is a fragile kind of beauty and flourishes naturally only in the early part of the life cycle. Happily, men can accept themselves under another standard of good looks – heavier, rougher, more thickly built … There is no equivalent of this second standard for women. The single standard of beauty for women dictates that they must go on having clear skin. Every wrinkle, every line, every grey hair, is a defeat.”

Ceres, Baccio Bandinelli, 1552–1556; Venus and Cupid, attributed to Alessandro Allori, c.1570 (detail)

While the “prestige of youth” afflicts everyone at some point in their lives, we are trained to critique a woman’s appearance at a much higher resolution than men. Men are allowed to age, women are not. Modern advertising and centuries of male-dominated image-making encourage us to view women’s infallibilities under a microscopic lens and to deride them when they fail to negotiate the shame of ageing. Despite the best efforts of the body positivity movements and cultural push towards diversity and inclusion, we’re still a society obsessed with youth. Efforts to delay ageing through invasive cosmetic surgeries has become normalised, sometimes even positioned as an empowering feminist choice. Year on year, getting “work done” becomes more accessible and more acceptable, spoken about casually among friends and peers as if it were akin to going to the hairdresser. Naturally, this puts even more pressure on women to conform.

Last year, iconic 90s supermodel Linda Evangelista took to Instagram to announce she was suing the company behind the popular cosmetic procedure, CoolSculpt, saying she was plunged into the “lowest depths of self-loathing” after it backfired and left her “brutally disfigured” and a “recluse”. It’s unsurprising yet tragic that a model who was feted for being genetically blessed for decades—who notoriously joked that she wouldn’t get out of bed “for less than $10,000 a day”—would lean on cosmetic surgery to assist her in looking years younger than she is. But of course, that’s precisely what has kept her contemporaries at the pinnacle of the fashion zeitgeist even as they enter their fifties and sixties. Hers is the rare cautionary tale of the procedure that goes wrong, and a reminder that loneliness and self-loathing are inevitable risks when you operate in an industry that demands and praises perfection.

Berger’s teachings still hold tremendous weight in our image-obsessed culture. You only need to look at the most followed women on Instagram to see which sex still exists to be looked at while the other gets to do the looking. Yet it would be remiss not to pause and appreciate the fact that better representation is well underway. In the cover shoot for US Vogue’s September issue, a diverse and ebullient group of models are seen laughing and applauding, among them trans-identifying model, Ariel Nicholson, and Yumi Nu, the first plus-sized Asian model to be featured in the magazine. “What stands out about the women on this cover is that they’re not reducible to kind; each is a unique superstar with her own story to tell, of which her beauty is merely a part,” writes Maya Singer. This image shows that we’ve come a long way since the homogenous beauty ideals, calculated charm and come-hither look of Titain’s goddess. Slowly but surely, she is being transformed from object to subject. Her gaze is her own.