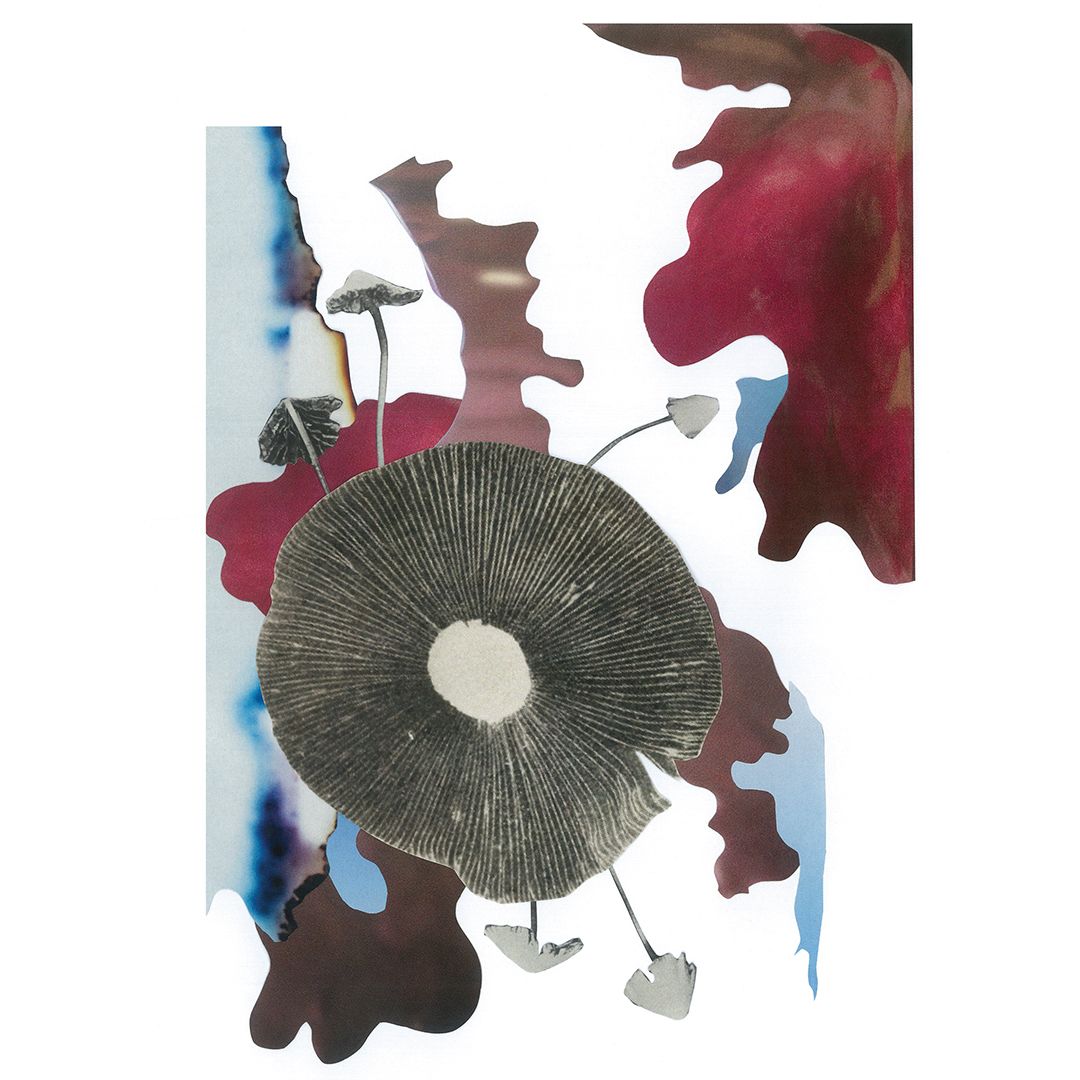

Inside The Magic Mushroom Revolution

Is psilocybin really the psychological white knight we’ve been hoping for?

I realize I’ve probably taken too much when I find myself transfixed by my fingernails. Specifically by the red nail polish I paid a nail practitioner $40 to lovingly apply earlier in the day. The colour is suddenly mesmerising. I am hiding out in the bathroom of a house party that has been staged to maximise tripping. (The hosts have imported a selection of blow-up plants and animals and scattered them across the premises.) Eventually, after God knows how long absorbed by my own fingers, I slowly move to a couch where I spend the next six hours surveying the room. I feel like I’m on a VR roller-coaster; I’m moving at great speed despite not actually moving at all. When the blow-up panda suddenly whizzes past me, now inexplicably flanked by a trio of purple comets, I try not to vomit.

That was 2015, and my first time taking magic mushrooms. The experience put me off for years, which was easy enough in a time when recreational MDMA reigned supreme. If you’d told me then that one day I’d be in an email chain with a woman I’ve never met organising a time to attend a ceremony wherein she’ll give me a high dose of mushrooms and take me on a guided trip to heal trauma, I would have laughed—and been slightly terrified. But all around me, friends are doing it. Some of them are having regular psychedelic therapy, some are attending ceremonies, and a few are micro-dosing LSD or psilocybin (the part of magic mushrooms that makes them magic) regularly to treat mental illness. Others are doing it instead of having that final glass of wine at the end of a dinner party.

Psychedelics, also known as hallucinogens, have been becoming more popular in recent decades. But with more people reporting mental ill-health and access to health services due to the Covid-19 pandemic becoming increasingly limited, the conversation has entered the mainstream. We’ve been taught to fear psychedelics, but as late as 1960 they were fully legal in the US and widely regarded as a promising line of psychological research. Back then, many believed they were in the midst of a psychedelic revolution.

As fast as it took off, the ‘free love’ movement that spread across the US in the ’60s began to crumble, and in 1970 the United States Congress passed the Controlled Substances Act, banning the manufacture and sale of all psychedelics. At the same time, companies making the drugs abruptly closed their research centres, and in an effort to deter people from seeking out the now-illegal drugs newspapers began and psychotic episodes. Psychedelics—and people who used them—garnered a bad reputation. Most people had heard a ‘bad trip’ story (much like mine) and few cared to experience their own firsthand. Research into psychedelics as a powerful psychological tool was put on the backburner, until in the late ’90s underground rave communities quietly began experimenting once again, despite enduring stigma and prohibition.

Though they are largely still illegal, medical research into the therapeutic benefits of psilocybin and other psychedelics, including MDMA, LSD, ayahuasca and ketamine, has been gaining traction over the last decade—particularly in the last five years. A 2017 paper published in Mental Health Clinician reported that psilocybin could be an effective alternative agent to manage mental health conditions including anxiety, OCD, alcohol use disorder and suicidality. Today there are psychedelic retreats for grief-stricken parents, people suffering specific traumas, or, as documented in Gwyneth Paltrow’s 2020 Netflix series The Goop Lab, for the well-off and wellness obsessed. In 2020, the US state of Oregon made history when voters passed a ballot allowing the manufacture, delivery and administration of psilocybin for therapeutic use. The law made Oregon the first jurisdiction in the world to lay the foundations for legalising psilocybin. In September 2021, Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) released a groundbreaking report concluding that MDMA and psilocybin administered under controlled conditions show promise in the treatment of certain mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression and PTSD. Such research suggests that these drugs, when administered under the supervision of medical professionals, could be key in revolutionising mental healthcare. Change is afoot, and we may soon find ourselves in the midst of a psychedelic renaissance.

Advocates of psychedelics—so-called psychonauts— aren’t arguing for the recreational use or abuse of psychedelic drugs. Many of them likely wouldn’t approve of ceremonial use, at least publicly. Instead, they suggest that psychedelic-aided therapy, properly conducted by trained professionals, can be personally transformative. ‘What’s interesting about psilocybin is it’s very, very chemically similar to serotonin,’ said Dr. Alex Belser on a 2019 Psychedelics Today podcast interview. ‘It’s operating in the serotonergic system of the body where a lot of antidepressants work, too. But with psychedelics, you only take this medicine once, twice or three times. You’re not taking it every day. It’s not about suppressing symptoms, it’s about having a very profound experience.’ In practical terms, this profound experience involves multiple talk-therapy sessions with a psychologist before psychedelics are even introduced, a full medical evaluation to rule out family history of psychosis, a safe and comfortable spa-like setting for the administering itself, and follow-up talk-therapy sessions in the days after.

Clinical trials have yielded hopeful results, which in recent years have spurred further trials all over the world. While there is not yet conclusive evidence, psychedelics are increasingly regarded as less likely than stimulants to cause addiction or dependence. Emergency room admissions are exceedingly rare and usually turn out to be the result of short-lived panic attacks. In an advanced phase trial published in May 2021, patients in the US, Israel and Canada who received doses of MDMA during talk therapy were more than twice as likely than the placebo group to show reduced signs of PTSD. Researchers concluded that the treatment was a startlingly successful and potentially breakthrough form of therapy.

‘When properly conducted by trained professionals, psychedelic-aided therapy can be personally transformative.’

A 2020 study at Johns Hopkins University found psilocybin to be four times more effective than traditional antidepressants. In a 2016 study of cancer-related depression and anxiety led by NYU professor Dr Stephen Ross, 83 per cent of participants reported significant increases in wellbeing or satisfaction six months after a single dose of psilocybin; 67 per cent said it was one of the most meaningful experiences of their lives. Both drugs could receive approval for certain treatments in the US as early as 2023. When I speak to people about their own journeys in psychedelic therapy, many tell me about Michael Pollan’s 2018 bestseller How to Change Your Mind being a critical entry point for them. The book also pops up in academic discourse and is widely cited in online discussions on the topic.

I can see why. After listening to the audiobook in preparation for this piece I immediately texted my friend, Olly, and after a bit of cryptic back and forth was given the details of an energy healer who also works with psilocybin (to those in the know). Initiating conversation with drug dealers usually starts the same way: a vague initial introduction as you feel each other out, specific keywords omitted, something like I was passed your details from [insert name here] who I think you know... It can be awkward, but Olly, who first realised the benefits of psychedelics entirely by accident, insists it’s worth it. He first took a recreational microdose of mushrooms in 2017 and felt the social anxiety he’d been struggling with for years completely evaporate the next day. When he told his therapist, she referred him to Pollan’s book.

‘Around the same time, a friend had an experience with psilocybin to treat depression and said it was like taking part in a miracle,’ Olly tells me. Rather than attending psychedelic therapy, which would have resembled a conventional one-on-one psychotherapy session (plush couch, gentle music, at least one trained psychologist in the room) he now attends ceremonies led by a shaman. Others are in the room with him during the ceremonies, each on their own psychedelic journey. The shaman, too, takes the drugs. ‘A lot of what makes ceremonies sometimes great and sometimes quite challenging is the presence of other people having their own, very different experiences,’ he explains.

These days you don’t have to look far to find positive examples of psychedelic experiences to combat the historic bad trips your uncle says he had in the ’60s. But in an unregulated and largely underground industry there are important issues to be addressed. When psychedelic therapy operates beyond the boundaries of legal practice, who decides on and implements measures to ensure safety? Who advises on best practice? In any therapy context, the subject is necessarily in a position of vulnerability. Add mind-altering psychedelics to the mix and the likelihood of being able to navigate out of a dangerous situation drops significantly.

As Pollan explains in his book, the importance of setting cannot be overstated. It’s also essential to build trust and rapport with your therapist beforehand. As I’m finishing this piece, New York magazine has released the first season of an investigative podcast series, with its first season hoping to expose the dark side of the psychedelic revolution and the troubling history of some of the movement’s leaders. Cover Story: Power Trip is an essential if difficult listen, focussing on a culture that has historically swept both sexual and psychological abuses under the rug. These abuses of power in this largely unregulated and underground movement confirm just how essential legal and medical frameworks are going forward. Conventional antidepressants aim to relieve the symptoms of depression, rather than ‘solve’ the root cause. They work for millions—between 40 and 60 per cent of people notice an improvement in symptoms within six to eight weeks as per 2018 research published by leading medical journal The Lancet—but can come with a host of side effects.

For some they simply don’t work, with as little as 10 and as many as 35 per cent of patients reporting treatment-resistant depression. Maddison* (30) spent close to a decade trying different medications to treat her depression with no success. Instead of helping, the medicine she was prescribed would often have the opposite effect, sending her into manic states lasting weeks at a time. ‘The depression was actually easier to deal with than some of the spirals the meds would send me into,’ she says. When someone suggested she try psilocybin, she was hesitant but ultimately decided to try it, with a dosage and treatment plan advised by her psychotherapist. ‘For the first time in my life, I understood my friends who went on antidepressants and two weeks later their lives had changed. I’d never felt that kind of “come to God” moment until that point,’ she explains.

Maddison, Olly, Michael Pollan, and an array of people whose testimonies I’ve read, all say that one of the most useful qualities of psilocybin is its ability to dissolve the ego and allow the user to observe one’s self from the outside. It can give people the ability to see different perspectives on life-changing matters such as terminal illness, mental health or trauma, and it’s something Olly has experienced firsthand. Not only does he feel more connected to friends and family after using psilocybin, he also feels more himself. ‘There’s an image people have of psychedelics—and being a psychonaut—of being kind of glazed over, becoming a bit distant from life and disconnected. But my experience has been the opposite. You feel this incredible return to yourself in the days and week afterwards, like you’re so connected to your life and what it’s about.’

It’s a pitch that’s hard to ignore. I was skeptical about ever undertaking psilocybin therapy myself, but after my research and interviews I feel compelled, if not yet entirely convinced, and so I send off an email request for my own mushroom ceremony. Here’s hoping there are no celestial flying pandas in attendance.

*Names have been changed