Girl on Film

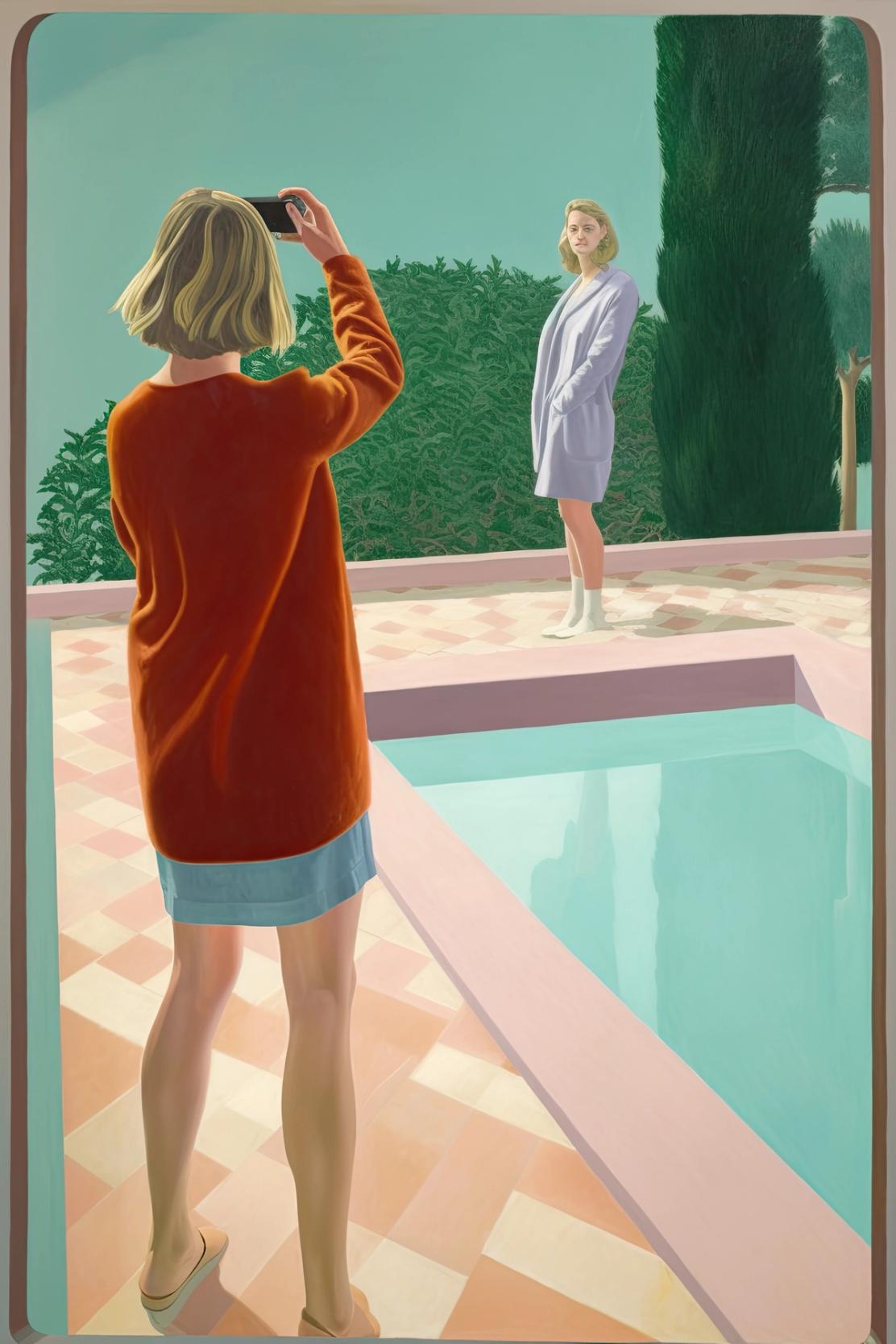

Elfy Scott explores our inherent—or perhaps not-so-inherent—desire to perform online. Whose gaze is it when we’re wielding the cameras ourselves? And what impact does the selfie have on the self?

It starts like this. On a day when my hair is sitting well. Or maybe when I’ve done a shockingly good job of my liquid eyeliner. Or maybe I’ve been invited somewhere unusually fancy and I’m wearing something other than track pants. I’ll lift my iPhone camera to my face and attempt to document the little triumph of looking—feeling—abnormally good. Only, these days it never quite works.

I’ll make a couple of attempts at looking sultry and that feels, well, dumb. I’m not a sultry person, am I? Why am I trying that face on? I never look like that. I’ll tilt my head to the side, maybe in some sort of half-hearted attempt to look more casual about this performance, only, it means that my face ends up looking like I’m stretching to escape the photo, as though my hand is some sort of tyrannical entity trying to document my head while my head tries to evade the frame. That’s weird. Ultimately I’ll settle on a light-hearted smirk (possibly an attempt to communicate myself as a fun person?) with a small tilt that says, ‘The selfie is happening, but it’s not like I’m taking it seriously!’ Sometimes I’ll publish it on Instagram with a self-deprecating caption. Most of the time, I’ll settle into the idea that the photo will never look as good as I thought it could in my head, give up, and trash a set of 25 photos that have done very little except waste 15 minutes of my day and left me feeling fairly shit about how I look.

I don’t remember the first time I took a photo of myself. I’m sure for the vast majority of women in my generation it would be difficult to pinpoint the exact moment, or the precise technology we were using, the first time we realised that we were able to capture our own faces looking a certain way, and conveying something about the type of person we wanted to be.

For years, many of us have welcomed this process into our everyday lives. It’s become a near-indispensable part of how we choose to perceive ourselves and, in turn, aim to be perceived. We must be the most self-documented people that have ever lived. And beyond our own awkwardly outstretched arms, our celebrity and online culture is saturated with selfies.

Kim Kardashian, one of the most famous women in the world, has built a huge part of her fortune by taking photos of her own face. So much so that in 2015 she famously published a collection of these under the title Selfish. An online description of Kardashian’s coffee table book describes her as ‘a natural leader of the selfie movement’, which is a surreal claim—but it probably isn’t disingenuous to describe taking photographs of yourself as a ‘movement’, all things considered. A lot of us spend an absolutely wild amount of time taking photographs of ourselves. Research has found that women aged 16 to 25 spend up to five hours a week taking selfies and sharing them on social media.

My own journey with selfies probably started with the Photo Booth app on my dad’s desktop Mac, with which I would apply absurdly high-contrast filters to create immensely satisfying images of my face with no visible plane tying together my eyes, nose and lips. Every young woman dreams of facial features that look like smudges floating together.

Later, when social media entered the picture and inexorably captured 100% of my teenage brain’s attention, I would take moody selfies for Myspace with my chin tilted downwards to exaggerate the black eyeliner hugging my bottom lids, trying to emulate ‘scene’ and emo girls who were much, much hotter than I could ever hope to be. Taking photos of yourself is so natural to so many young women, so socially acceptable—no, socially encouraged—that it’s almost absurd to look at it with any critical appraisal of what we have participated in. The selfie is a bizarre, fraught thing. It can be vain, political, destructive, or assertive, depending on however you might happen to think about it. But the thing is, we so rarely do think about it.

The first question I suppose would be logical to ask is: why do we feel compelled to engage in self-documentation at all? What is it that’s driving us to pick up a paintbrush or a pencil or an iPhone and capture our own faces for the world? I posed the question to professor Sarah Diefenbach, a market and consumer psychologist from the University of Munich who has studied selfies as a psychological phenomenon.

Diefenbach tells me that it comes down to a fundamental psychological need for self-presentation: the need to communicate who we are to others. There are two aspects of self-presentation, both relevant to what happens when we choose to take photographs of ourselves. The first is self-promotion, which basically means highlighting your accomplishments or abilities; all of us want to be seen as capable, intelligent and talented, and selfies give us ample opportunity to do that (or, at least, try to do that).

The second aspect is disclosure, or revealing parts of your emotional self to the world. We take photographs of ourselves because we aim to strike up sympathy, trust, or appreciation from others. ‘In contrast to self-promotion, self-disclosure does not aim to present the best ‘polished’ self, but rather aims for sympathy through openness and ‘natural’ insights into the self,’ Deifenbach tells me.

Both aspects of self-presentation seem like reasonable things for our social brain to desire from other people: the need to be seen as good, as well as the need to be seen as relatable. Then, the next question to ask is: does engaging in this process actually make us feel good about ourselves? Overwhelmingly it seems as though it doesn’t.

When I put a callout on social media to discuss this topic, I found that my experiences attempting to self-document were echoed by many women who found the process equally as abominable. They reported feeling distraught by attempts to take selfies, saying that they quietly compared the success of those photos to the selfies they saw others publishing online; when they couldn’t achieve what they perceived to be the same level of attractiveness, it made them feel worthless—the same kind of emotional reaction that I tend to experience.

The research backs up what these young women have told me: there’s a paradox at play here, where we keep participating willingly and frequently in something that makes us feel bad. One 2018 study found that women who took and posted selfies to social media reported feeling ‘more anxious, less confident and less physically attractive’ afterwards, and those feelings didn’t even improve when participants were given the opportunity to edit their photos.

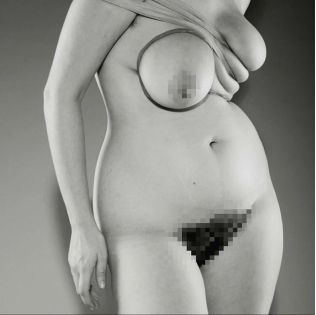

Social media has always provided a particularly unique and horrific space in which to compare yourself to others, and to be compared against others. We know that exposing ourselves to social networking sites results in high levels of weight dissatisfaction, a drive for thinness, and unhealthy body surveillance (particularly in young women). But it goes even further than that. People who engage in taking selfies are at risk of internalising an external viewpoint of their own bodies (otherwise known as self-objectification), adopting a perspective that’s detached from what we tacitly understand about ourselves. It’s a state that puts us at higher risk of obsessively assessing our bodies and leaves us more vulnerable to developing eater disorders. And yet, we continue to perpetuate the cycle—why?

The truth is that taking selfies is a multifaceted process that goes beyond the desire to document feeling hotter than usual on any particular day. And when we’re motivated to take photographs of ourselves for more fulfilling reasons, it actually tends to make us feel good. Whenever we pick up our phones to mark a memory, have fun or assert our independence, we’re acting in good faith with ourselves; taking selfies can become less about chastising ourselves for physical flaws or comparing ourselves to others, and more about focusing positively on those aspects that display our individuality. And for people who belong to marginalised communities, who have physical features that have been routinely ignored or maligned by traditional western beauty standards, it can also be an undeniably politically empowering act to take and publish a selfie; to proudly document and broadcast parts of the face and body that set certain people apart is a form of protest that shouldn’t be undermined.

When I ask online about people’s selfie behaviour, a friend sends the following quote by British novelist and art critic John Berger: ‘You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting ‘Vanity’, thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for your own pleasure’. She tells me it motivates her to feel good about capturing her own image, and I understand what she means. As women we’re taught to so broadly accept the simultaneous commodification of images of ourselves, as well as the condemnation when we’re the ones capturing those images, that it can feel like a cool rebellion to be proud of our own images and reclaim the vanity.

Ultimately, it’s not that taking photographs of ourselves is inherently dangerous or powerful; it’s all determined by the motivation and awareness we have around that activity. As for my own motivations for taking selfies, I think they’ve largely failed and it’s difficult to envision how I can alter the way I approach my own behaviour. Mostly, I think it’s just up to me to avoid it at all until perhaps the rare days when I know that I’m doing it for a reason other than just trying to, well, look hot. Because it’s not the most important thing, and because it doesn’t always work.