Janicza Bravo didn’t grow up dreaming of becoming a filmmaker. She wanted to be an actor. ‘Actually, I wanted to be a clown before I wanted to be an actor,’ she qualifies. ‘And I wanted to be a track star before all of that.’ It’s a writer’s job to extrapolate on anecdotes like these, to give them a narrative arc where perhaps there isn’t one. But there is something satisfyingly Bravo-esque about this trajectory: the discipline of the athlete parlayed into the naivety of the jester; the vulnerability of life in front of the camera traded for the omnipotence of life in the director’s chair. This, in many ways, goes about explaining who Janicza Bravo is, if not as a human being then at least as an artist who makes confounding films that are at once hilarious, horrifying and heartbreaking.

Bravo spent her early childhood in Panama, between the seaport city of Colón and the US military base in Panama City where her mother worked. At 12, Bravo and her parents returned to the United States, settling in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, in a home that was full of screens—‘there were four TV sets for the three of us’. Bravo remembers being particularly moved by The Wiz, Sidney Lumet’s chronically overlooked (by the white world at least) reimagining of The Wizard of Oz, starring Diana Ross as Dorothy. ‘That movie was very important in my development,’ says Bravo. ‘Perhaps it was seeing myself but not knowing I was seeing myself. I mean, to be in Diana Ross’s shoes? Splendid.’

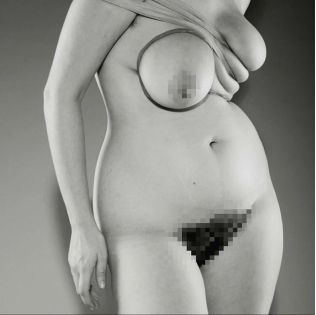

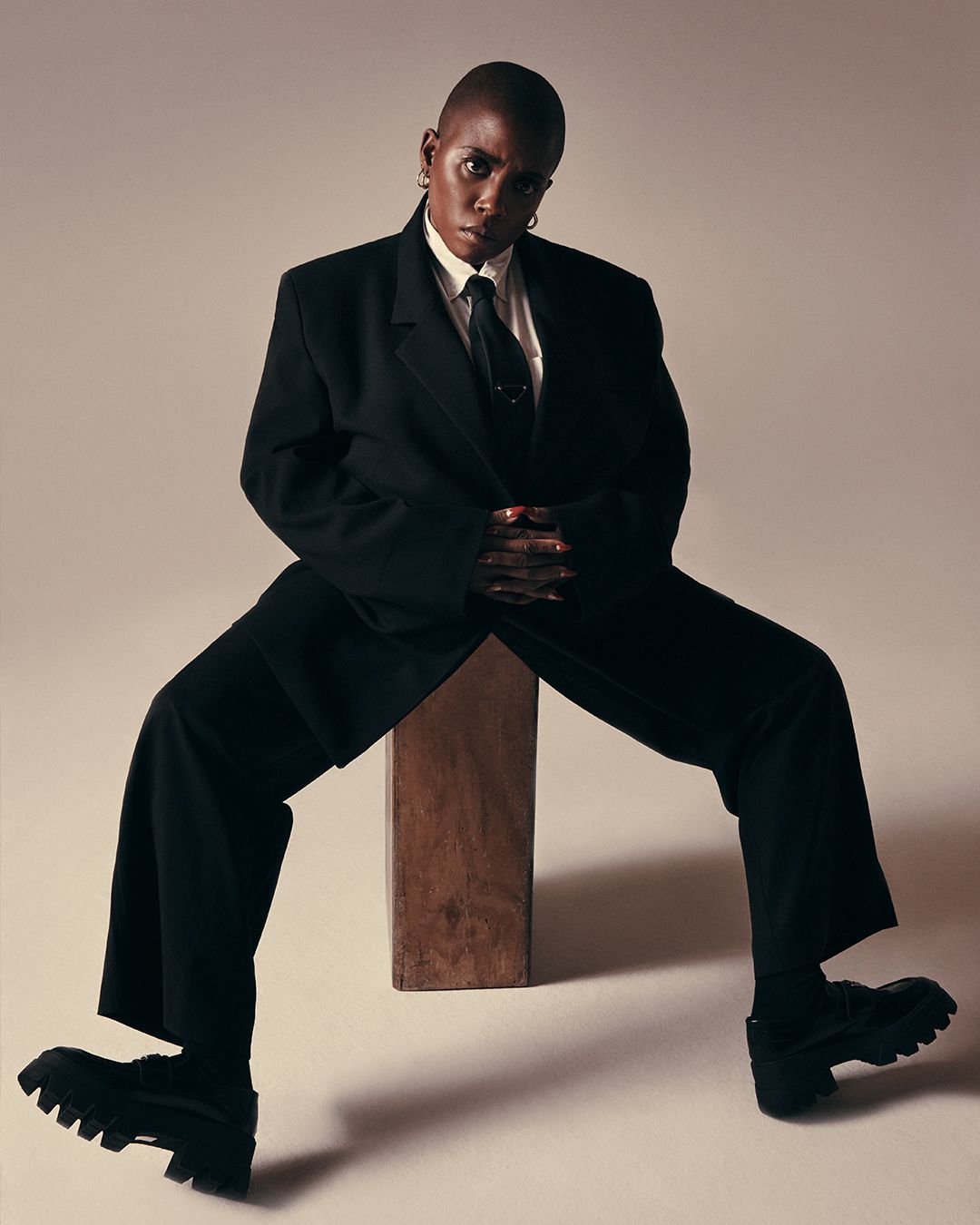

Janicza Bravo as Jean-Luc Godard

Having her sights set firmly on acting, Bravo attended the Playwrights Horizons Theater School, part of the prestigious Tisch School of the Arts, where she majored in directing, costume and set design. ‘Acting for me was accepting a loss of control,’ she reflects now. ‘I could set the path I meant, but once you introduce other performers, objects and collaborators, it’s no longer just yours.’ Endeavouring to create things that could just be hers, Bravo abandoned acting after college, instead moving into wardrobe design and styling. On a commercial shoot for the New York Lotto, she met the actor Brett Gelman, who she would later marry (the couple divorced in 2018). Bravo and Gelman’s relationship doubled as a furtive creative partnership, with Gelman starring in a trio of iconoclastic short films directed by Bravo in the early 2010s. (In a 2015 Reddit AMA, Gelman wrote that he and Bravo ‘decided to work together because she asked me to, and I can never turn down a genius’.)

Bravo had, in a burst of intense creative energy, written the screenplays for 10 short films over a period of eight months. ‘I hadn’t gone to film school, so I kind of imposed this idea of film school onto myself,’ she later explained. Among the buzziest was 2013’s Gregory Go Boom, an unnerving short starring Gelman and Michael Cera. The latter plays a wheelchair-bound man on a series of haphazard dates, culminating in a thwarted sexual encounter, and ends with Cera self-immolating in the desert, his burning body the film’s searing final shot. It’s unsettling. But also funny. But also tragic. The kind of film you carry around in the pit of your gut for the rest of the day.

Janicza Bravo as Federico Fellini

Bravo and Gelman would work together again on the script for Bravo’s feature debut, Lemon (2017), a skewering, irony-laden takedown of white male entitlement with Gelman starring as the lead, an insufferable struggling actor named Isaac. The film was one of the most-hyped releases at Sundance that year, with Criterion (which quickly snapped up the streaming rights) dubbing it ‘one of the most audacious feature debuts in recent memory’. Lemon, like Gregory Go Boom and Bravo’s other shorts, exhibited a trademark style that was astonishingly self-assured, a major theme of which is Bravo’s ‘anthropological relationship to whiteness’. Through her lens, the spectacle of white male privilege teeters between engendering pity and disgust.

It’s no secret that the history of Hollywood is almost exclusively white and male. But the tension point between this homogeneity and Bravo’s life experience has only ever emboldened and strengthened her art. ‘Did I grow up watching movies directed by white men? Yes. Are there white men whose work I admire, that has forever changed my life? Absolutely. But at no point have I played to any gaze that was not my own,’ Bravo asserts. Still, navigating the film industry as a Black Latina director is no small thing. ‘A couple of friends were talking recently about imposter syndrome, and it’s an idea that is so foreign to me,’ Bravo says. ‘Because I think with imposter syndrome comes some feeling of having belonged, or having [had] an invitation. But I am still regarded as not belonging in a lot of spaces that I move in and out of. In that sense authorship, which is what ‘auteur’ is, is the only thing that I get to have or own.’

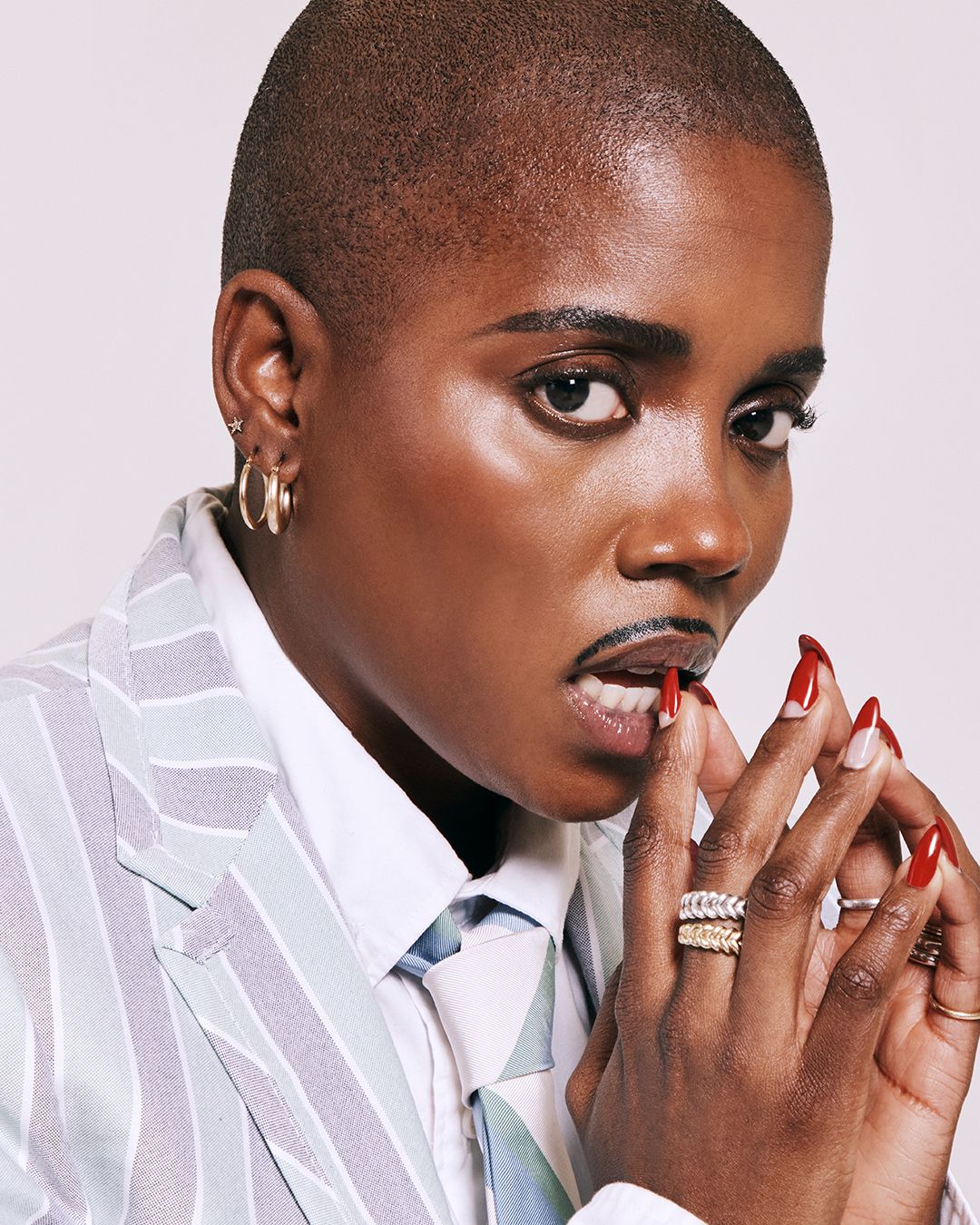

Janicza Bravo as Spike Lee

The road to Bravo’s sophomore feature, Zola, was as ‘long and full of suspense’ as the film itself. It began in 2015 with a viral Twitter thread by Aziah ‘Zola’ King, detailing a debauched trip to Tampa, Florida that King took with a fellow stripper named Jessica. In a cinematic first, rights to the Twitter thread were quickly snapped up by James Franco, who was slated to direct an adaptation. King’s Tweets are hilarious and messy, but they also lay out a complicated, nuanced story with a Black sex worker at its centre. And so King’s fans—who at that point included Missy Elliott and Solange Knowles—were justifiably concerned when Franco unveiled a eight-person production team, all of whom were white.

The Franco adaptation wasn’t destined to be. Production was halted amid allegations of sexual misconduct against the actor, and in 2018 Bravo, who had loved King’s tweets and initially pitched to direct the adaptation, was hired. She tapped Jeremy O Harris, a friend since way before he was the Tony-nominated toast of the New York theatre scene, to co-write the screenplay. ‘Jeremy and I met at a party, where he was on a date that had gone south,’ Bravo explains. ‘We found each other in a kitchen and he liked my laugh and sidled up to me.’ Harris was on the east coast finishing up his studies at Yale, while Bravo was in LA, so the pair texted and voice-noted each other ideas (‘I think he tried to FaceTime me but I loathe that way of communicating,’ laughs Bravo), and developed the screenplay from there.

Janicza Bravo as John Waters

She auditioned 800 actresses for Zola before casting the incandescent Taylour Paige in the role (alongside Riley Keough, Nicholas Braun, and Colman Domingo). It took three years of halting pre-production and only 27 days of shooting for Bravo to direct Zola. But, thanks to seemingly endless pandemic-related release delays, it wouldn’t reach screens for another two years. ‘Working in this space is about accepting that time is often glacial,’ Bravo quips. Still, the wait was worth it. Zola was met with nearuniversal acclaim. Richard Brody at the New Yorker called the film ‘ingenious and audacious’ (there’s that word again), while The Telegraph dubbed it a ‘whipsmart critique of the social media age’.

The film’s success opened Bravo up to a new slew of work. She was commissioned by Miu Miu to create a short film as part of its Miu Miu Women’s Tales initiative, which includes in its ranks Agnès Varda, Ava Duvernay and Miranda July. Rian Johnson and Natasha Lyonne tapped Bravo to direct the finale of their hit murder-mystery series Poker Face. Still, Bravo’s sense of success is rooted in something a little deeper than industry accolades. ‘I’m trying to avoid that question [of what I’m working on] at the moment, because we’re creating a culture that is so geared towards consumption that it allows very little room for space,’ she explains. ‘What I want to start saying is ‘nothing, I’m working on nothing’. I’m working on liking myself a little bit more than I did before.’

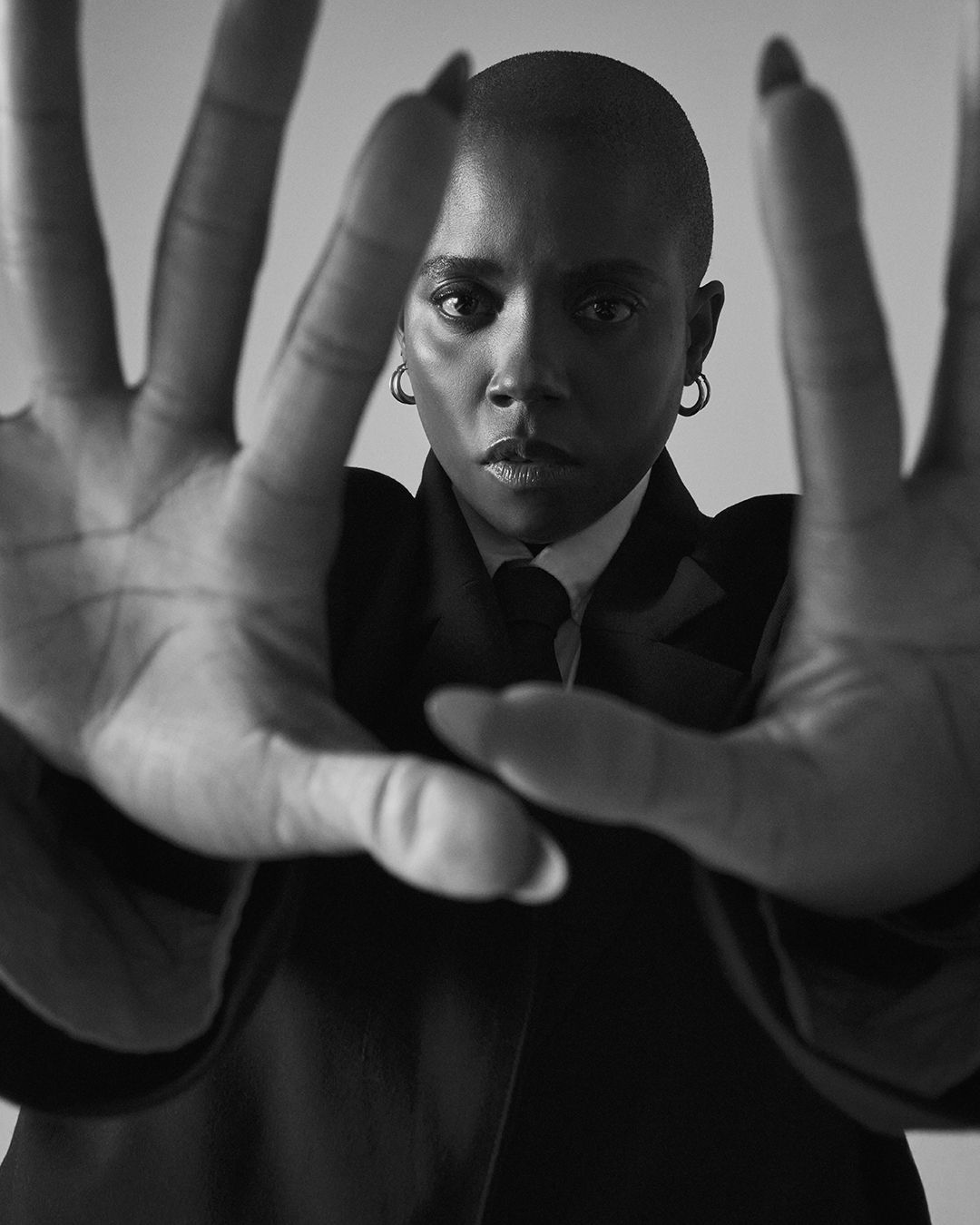

Janicza Bravo as Alfred Hitchcock