Le Nouvelle Vague

Rosalie Varda, daughter of French New Wave cinema icon Agnès Varda, sits down with Par Femme to talk about her mother’s legacy, her unorthodox childhood and why we must fight for art. Interview by Oliver Mol.

I would like to begin this piece by saying Rosalie Varda, daughter of celebrated filmmaker Agnès Varda—considered the mother of French New Wave cinema—and adopted daughter of filmmakerJacques Demy, is one of the most passionate, interesting and humble people I have encountered in recent memory. She has spent the past 40 years working across cinema, in costume design, and as a producer and activist helming Ciné Tamaris, the production company Agnès created in 1954 to produce her first film La Pointe Courte. In the final years of Agnès’s life Rosalie produced Faces Places, for which she received an Academy Award nomination, and Varda by Agnès, which won a Women Film Critics Circle Award for best documentary by or about women.

It should go without saying that Rosalie Varda tirelessly and profoundly believes in the power of art. Rather than make herself the subject, she has preferred to work behind the scenes, supporting others, breathing life into projects, making them appear effortless.

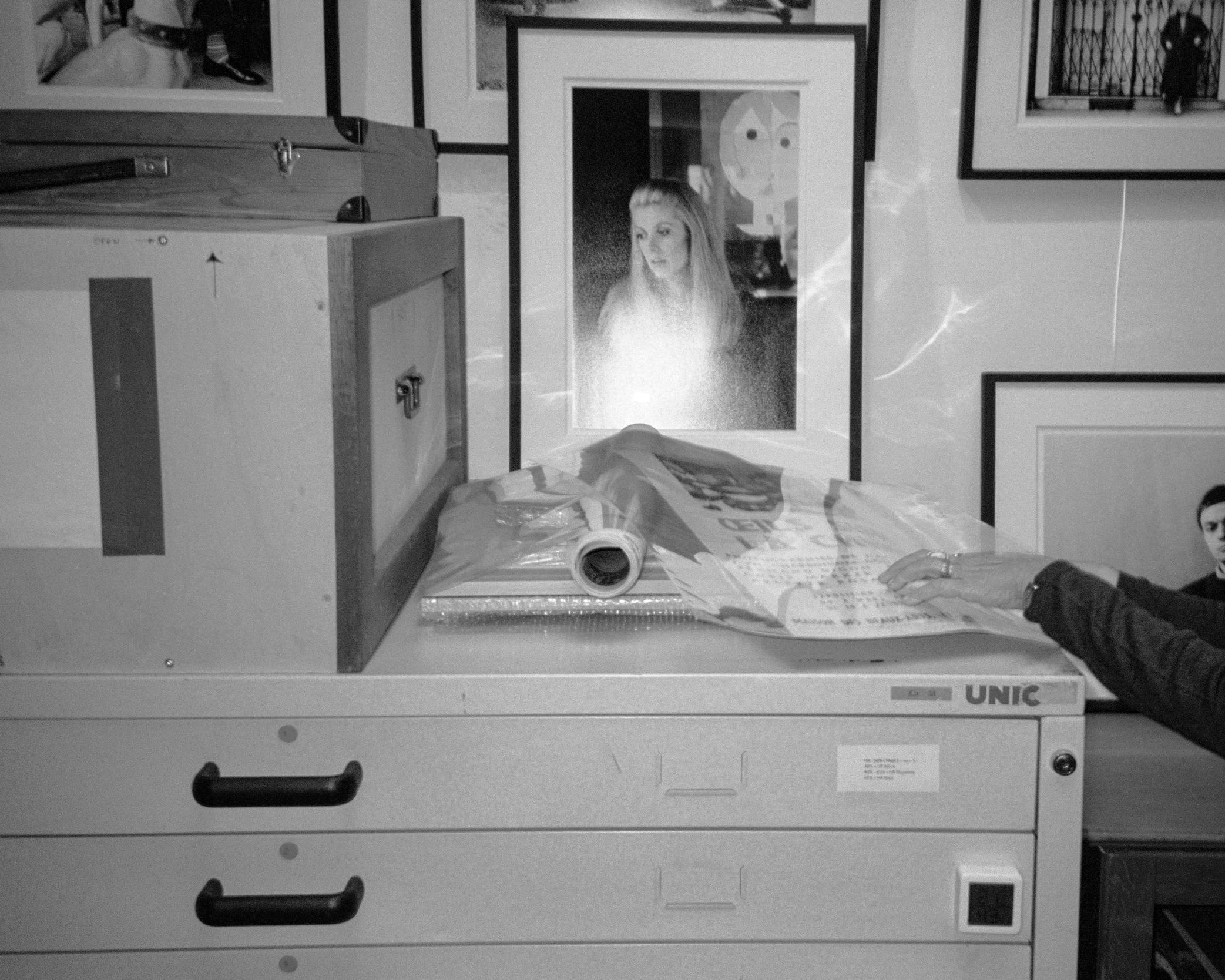

The interview you are about to read occurred over several hours at the Ciné Tamaris in the 14th arrondissement of Paris, next to Agnès Varda’s former home. Rosalie made herbal tea, and we discussed the Varda artistic legacy, her childhood and her commitment to the redemptive power of art. Afterwards, she showed us her mother’s photographic archive, which included portraits of Salvador Dalí, Jean-Luc Godard, Catherine Deneuve and Bernardo Bertolucci, among others. Not surprisingly, after Holly [Gibson, Mol’s partner] took photos, we left the encounter feeling elated, and as we made our way back to the metro we discussed and felt profoundly moved by her selfless vision, energy and warmth.

PF: I wanted to start with your mother Agnès Varda’s exceptional last film, Varda by Agnès, which you produced. The film works as a fascinating and poignant retrospective that allows Agnès to discuss the creative decisions behind her extensive body of work, and I was particularly moved by her statement that all her art came from three desires: to inspire, create and share. I remember, after that film, feeling the same way I felt after the recent Joan Mitchell and Claude Monet exhibition at the Louis Vuitton Foundation: tremendously inspired, as if your mother had given each one of us the permission to remain curious, to search for meaning and truth, and to create. What was it like working with your mother on this film? And how did it come about?

RV: Well, to work with my mother has been a long journey, and it’s interesting because in the world of art and creativity it’s quite normal for actor parents to have actor children, but I didn’t want to be an actor when I was little. I hated to be in front of the camera. My mother took a lot of pictures of me when I was a child, and when I had the age to say, ‘No, no that’s finished’, there were no photos of me for a long time. So I had a normal childhood. I did art studies. I became a costume designer. I did my own life. I had three boys, and now I am a grandmother. But over my life I worked in theatres, cinema, publicity, music. I made a lot of costumes for the opera houses, and I worked with my parents on films. With Agnès, I did the costumes for Vagabond, One Hundred and One Nights, and with Jacques Demy I did the costumes for Une Chambre en ville, La Naissance du jour and Trois places pour le 26. I also worked with my brother on a film called Americano. Then in 2003 the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist asked Agnès to create an installation for the Venice Biennale, and in 2006 the Cartier Foundation [for Contemporary] Art asked Agnès to do an exhibition. She asked me to work with her and we created the installation together. It was the first time working together directly, and it was so soft and nice. After that I worked with her on The Beaches of Agnès, and after 2008 I began to take care of the company [Ciné Tamaris]. She had created Ciné Tamaris to produce her first film in 1954, and I thought it was a way to share real time with her, you know, not speaking about what we were going to eat, what was going to be the holidays, did my kid do well in school, or is someone sick; we were going to talk about the rest, which is creativity, sharing its creation, travelling and hard work. I thought, if I can give her the opportunity to only work on the creativity, then I will take care of all the rest.

We were very good partners in crime. She was a very old woman with a lot of energy, but of course sometimes she was very tired. So we decided that we had to work with her rhythm. We shot two days a week, sometimes three. In 2010 we travelled a lot to present The Beaches of Agnès, and she was just energy, energy. In 2014 I said, ‘Let’s do a marathon until the end’, because I knew of course at one point she would die. I was thinking something like: can we prepare with the person alive for the death? I thought it was a challenge and we decided the last journey would be very joyful. I knew one day it would be finished, but until then we would run, not walk. We would run around the world. We would do films. You know I produced Faces and Places, did you see?

Yes, it’s incredible.

Shooting with [co-director] JR was a big adventure. Imagine, he was the age of her grandson, and he would challenge her. ‘Oh, come on’, he would say, ‘You walk too slow!’ And she would say, ‘I can’t walk any faster!’ This was fun. But it was also a very practical adventure, because when you take care of an old person you have to protect them. I was also like an assistant making sure she could do the project exactly as she wanted. And I found the money, which was a new challenge for me.

To say it more quickly, I had the opportunity to share my mother’s life, to share the path of how the brain functions, how one idea brings you to another idea like little stairs. If I hadn’t worked with her I wouldn’t have seen the fascination and empathy she had for others, and how the younger generation just loved her. I would not have seen anonymous people stopping her in Shanghai saying, ‘You are Agnès Varda!’ Or in New York a woman saying, ‘Look! I did a tattoo of you on my arm!’ I would not have shared those joyful moments of life.

That’s really beautiful.

When she was there in front of me, I had already done the journey of losing her. So when I lost her physically I was not sad. I knew that what she had done as a photographer, as a filmmaker would stay. And this is what we do here in this company. We share her with new audiences.

Agnès famously said in her biography that she had only seen about 10 films prior to making her debut La Pointe Courte, considered a stylistic precursor to the French New Wave. I love this because it’s wild and impressive, and because it relates to something Rick Rubin said recently in his book The Creative Act: ‘Often, the most innovative ideas come from those who master the rules to such a degree that they can see past them or from those who never learned them at all’. You were born four years later. What was it like growing up in the Varda household? And what is your relationship to this film, given Agnès created both of you more or less around the same time?

So first I would say you should look at her short film L'opéra-mouffe, which she did in 1958. She was pregnant with me when she made it, and she was very interested to show poor people, drunk people, homeless people in a neighbourhood of Paris. She was thinking these people had once been babies, they had been loved, and now we can’t even get next to them.

I was raised in a house of artists [who had] no children. My parents worked a lot and received a lot of people, and spoke about art and cinema and music. I had a very happy childhood, but I would not say that I had a normal childhood, because there were only adults around me, very well-known people globally. But this was my life, and I could not compare [it]. I was raised, and loved. I went to school like everybody. My mother never took me to school but it didn’t matter. It’s not the quantity of love that is important but the quality, and my quality was [a] very high level.

You know, it’s funny. We have a lot of photos of me and when I showed them to my kids, who did have kind of a normal life, they would laugh and say, ‘Oh my God, look at you and Jean-Luc Godard sitting at the table’, and I would say, ‘Well, yeah’. You realise later that maybe this is not what everyone has. I mean this was 1967 or 1968, and it was kind of a wild period. The Doors played a concert for my 10th birthday. People would take heroin and ask me, ‘Hold my hand, I am afraid of the needle’, and I would say, ‘Okay, no problem, I will hold your hand’. I think now all the parents would be in jail, but it was another period and I am very against the judgement that can happen 40 years after the situation. My parents were very caring people with others and with themselves, but I have some very funny stories to tell, so one day maybe I will do the autobiography.

I would love to read that! When you were growing up was there the expectation that you would be an artist?

No, I didn’t want to be an artist. I wanted to be a spy.

Maybe you were!

I wasn’t, but I was learning English, Russian and Chinese. This was about 1976, but then I thought, ‘No, I don’t want to do that’. I really was behind the scenes doing costumes and set design. You have to be very narcissistic to be in front of the camera, and I am not narcissistic so it could never have worked. Now, I take care of Agnès and Jacques’s archive. I travel and speak about cinema, and encourage new audiences to see old films.

What I love about your work is that you focus energy outwards. It really feels like your mission is to help and enable other people, and you make it look effortless.

Well, it’s a joy. And we are always tirelessly promoting. We have an exhibition on Agnès at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles, and then another at La Cinémathèque Française here in October, and there will be two more exhibitions on her at the Rencontres d’Arles photography festival. We work a lot to share the estate, to share the photos. She’s so sharp, you know. Every time I read something she wrote I think, ‘That little lady was sharp’.

It’s almost like she was creativity personified, and the way she used structure …

She worked hard, but she always said, ‘It should look easy. It should not look hard.’ I think this was important for her. Not to show the effort. Vagabond looks effortless. It looks smart, and how she structured her film using those seven long tracking shots, then always finished on an abstract object, which in many ways reinforced subtly the themes of each scene. I think cinema is not just pointing a camera, but the way you share the story, and the emotion you want to give. This is why I wanted to do her last film, Varda by Agnes, because she was always doing these conversations and masterclasses and she was fed up with doing it. I said, ‘Well, let’s do a film that we can share afterwards’. And I found it thrilling because each time we went to the university and filmed I would learn something new. She always said with each project she would think what is the best way of narration, and I really think a lot more directors should think about this. She was not an intellectual. She was a humanist, and I think Agnès really challenged herself to find each project in a very personal way.

You studied at fashion-design school Studio Berçot. What was that experience like?

I did fashion school, and then I began to be a costume designer, and at the same time I was an assistant to another costume designer. I worked a lot. I realise now that I worked a lot. Even though I did have my kids and everything, I did work a lot.

Would you change it if you could go back?

No, I would not change it. Maybe I would have had more than three kids, but I would not have changed anything. I think we are able to have everything in life if we want to, and I think my education gave me the energy and the brain to know that I could do everything. I could have a family and a love story and good stories and bad stories and kids and work and disappointment and everything working. My mother gave me a good education on that basis. She made a film for me for my 18th birthday called One Sings, the Other Doesn’t. It was my gift, and I think this gift was really important because it was a story about two women struggling for feminism, and it made clear that I could have everything. But still it’s difficult because [now] you see Afghanistan and you cry, you know, you see Iran and you cry. You see abortion rights in the USA and you cry, and you understand that it is a struggle that will never end. So now I look at the young generation and I think, these men and women will have to struggle together. It’s a hard time for democracy and it’s a hard time for peace. Culture is necessary and we need to fight for culture. We need to fight where we can. My little own thing, I fight here. For this. If everybody does a little bit we will not be in the big mess. I don’t know about you, but I don’t even want to look at the news anymore. Ukraine. Türkiye with the earthquakes. Did you see the 200- [mile] hole [caused by the Syria-Türkiye earthquake]? The planet splitting like this? And so then you ask: art, is it necessary? Yes. Will it save the world? No. Will it give you hope? Yes. I think we just need to know where we are. I work for the young generation. I work for the kids.

I just wanted to say that meeting you, it feels like you are doing exactly the thing you were put on Earth to do.

My mother said she had three lives: photographer, filmmaker, artist. I feel that I have [had] a lot of lives, too. I think [about] where I am today at 64. I am well, and I feel very young in my energy. My team is very young, and they protect me. I travel a lot, and I come back with my suitcase and they say, ‘I take your suitcase!’ I feel the love in this company has good vibes. You say this in English?

Yes!

Good. We’re not going to stop. Never. And I hope someone will take over after me.